Hardscrabble: Brutal Legend, Rugged Beauty

Herald Citizen, Cookeville, Tenn., Thursday, August 12, 1965

Denning, Charles. "Hardscrabble: Brutal Legend, Rugged Beauty." Herald Citizen[Cookeville] 12 Aug. 1965. Print.

By Charles Denning

Hardscrabble may not sound like the name of a fascinating scenic wonder.

But it is.

Through (sic) ‘hardscrabble’ is not a word in the dictionary (1), anybody in this part of the country probably has a good idea what it means, whether he is able to put it into words or not.

The word has a rural flavor, suggesting rough, stony land, a tough place for a farmer to make a living.

“I first saw the word in print a couple of years ago,” Robert Hawkins said. “I was on a plane trip and picked up a copy of LIFE magazine. Reading an article about Lyndon Johnson and the LBJ Ranch, the country around there was called ‘hardscabble land.’ Out of the gray past, without an orgin (sic) which can be definitely cited, the word had been applied as a name to a spot of geography not far from Cookeville.

Guided by Hawkins, of Algood, a son of William Hawkins, on whose farm in the southeastern corner of Jackson County Hardscrabble is located, we went there. Hawkins’ farm is just off Highway 135 to Gainsboro about 10 miles northwest of Cookeville and near Dotson (sic) Branch church and Cemetery.

Its ruggedness is the first thing you hear about Hardscabble. The approach through the fields in back of Hawkins’ barn, through the woods and winding into the hollows is not taxing. Getting down into the gorge and out again is a matter a bit different.

Second thing you’ll hear about Hardscrabble is the legend of the strange, brutal killing by moonshiners of a crippled boy who had innocently wondered upon their still in search of his mother’s cow.

With us went three boys, Hawkins’ son, John, and Randy Fields, and Mike Mabre, and an assortment of hounds, Plott, and beagle. The day was bright as the face of a new coin, sweet as an oboe tune, somewhat cooler than usual. The late-July sky, blue as October, was streaked sparsely with gauze-like clouds.

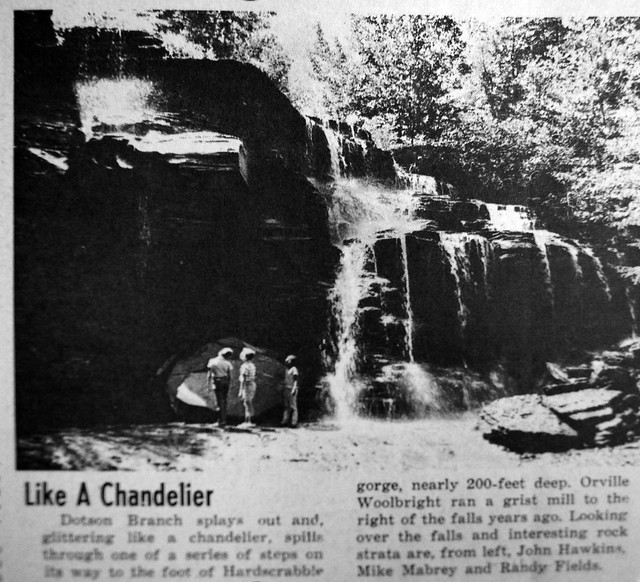

Beside blooming tobacco patches and tussling cornfields we passed, over what Hawkins called “stagger road” – the trail once taken by moonshiners coming from Hardscrabble with jugs slung in pokes over their shoulders. We found Hardscrabble a rock-ribbed canyon with the Dotson (sic) Branch falls, a stepped cascade at its head and a peaked, treacrowned (?) rock formation, unofficially (2) called “the pinnacle” near the mouth of the gorge.

Crossing the branch we took a twisting trail once plied on horseback by the late Walter Smith, of Cookeville, a mail carrier, down into the gorge at the foot of the falls. Orville Woolbright, who has a store now in the Dotson (sic) Branch community, once ran a mill on Hardscrabble Falls. Climbing the trail to “the pinnacle,” we crossed under a high, overhanging bluff and there found neatly stacked rocked slabs which has years ago enclosed the first pit of a still. Earlier we has learned that it was not at this still but at one under Pole Bridge Creek falls in a nearby hollow that the crippled boy had been boiled alive.

Up rock shelves we shunted to “the pinnacle,” which rises high and stands like a forecastle of a ship jutting into a swaying canyon. Not a mile from paved roads, the country is wild and lonely. On the wind-swept top we saw cedars dwarfed and maimed by gusts that sweep from the stony canyon. Somewhere a bird cried, “Sharp! Sharp! Sharp” – a judgment which struck through the leafy woods like a hammer on an anvil. But the birds tell nothing, nor the trees, nor the sky. Not even the wind, rushing out of the secret gorges silent as burial crypts, through (sic) it sometimes seems about to, like lips which tremble tensely on the verge of speech.

Under an overhang, we noticed crystallized alum (3) like white crusts and exposed mineral patches yellow as marigolds, rocks scaley with flakes of gray-green lichen.

After Hardscrabble, we trekked to the Pole Bridge Creek, down through a steep woods to the shallow, gravely stream, which we sloushed through to the falls. The cool stream flowed clearly, quietly. Minnow schools scattered shyly here and there in formation. Once a large fish, seen as little more than a shadow, hurried under a submerged rock. And the dogs routed a varmint of some kind, had a few minutes of excitement and ended up with nothing, milling about sheepishly.

Opposite Pole Bridge falls is Dave’s Bluff, named after one Dave Hamilton, reported to have died in a fall from the bluff one night years ago. Unable to reach the bottom of the falls, we learned over and peered into the chasm and the shadow under the overhang. We could spot no trace of the sill where the boy had been murdered. According to legend, pieced together from several sources, the crippled boy was searching the hill and hollows for his mother’s cow, strayed from her pasture. Tracing reports of those who said they had heard the cow’s bell, the boy happened upon the shiners, who apparently feared he would turn them in.

Opinions vary on how long ago the incident happened, from just after the Civil War to around 1900. But those who have had the tale handed down to them repeat it, embellished with horrific details, as if they been eye-witnesses. For a week or two, it is said, the boy was kept tied-up in a barn somewhere in the area of the still. Then the shiners, perhaps in a fit of drunkenness, made up their minds to destroy him. The (sic) built a fire under the mash boiler and, when the water was hot, stuffed the boy inside. In a wretched mania, the boy kicked the lid off. But one of the men replaced the lid, climbed up and sat on it until the spasms inside the boiler finally ceased. The boy’s bones were buried under a rock near the 50-foot, pony-tail falls emptying off the bluff above the still.

One account tells of an old man who, later, collected the bones and kept them about his place in a grass sack. The bones finally were throws back into Pole Bridge Creek, washed over the falls and lost it is said. Those who tell the story state positively that none of the men involved were ever charged with the crime. But there is one ending to the story, maybe invented by an over-zealous moralist, which contends that each of the shiners met retribution, as they died particularly bitter deaths. For instance, as the man who had sat on the lid died, four of five were required to hold him on the bed. “I see the crippled boy!” he screamed pleading, “Don’t let him get me! Don’t let him get me!”

“Hardscrabble,” the word seems to enclose all this in its meaning. And the legend of the crippled boy seems to fit well into the country both harsh and desolate and beautiful.

Notes

1) Though hardscrabble may not have been in the dictionary when this was written, it currently is and means "not having enough of the basic things you need to live" according to the Oxford Learner's Dictionary. URL: https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/us/definition/english/hardscrabble?q=hardscrabble; Accessed: 6/22/21.

2) The name Hardscabble is now officially the name of the pinnacle and the waterfall.

"U.S. Board on Geographic Names" U.S. Board on Geographic Names (BGN). N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Mar. 2014.

3) Old-timers had told me about "alum" under the overhands of bluffs before. They said it was collected and sprinkled on their fields as fertilizer. I saw the crystals when visiting Hardscrabble a few years ago and decided to satisfy my curiosity. I collected a sample and had it run through the XRD device at TTU. It came back as almost entirely gypsum. Here's a photo:

More Hardscrabble photos:

Denning, Charles. "Hardscrabble: Brutal Legend, Rugged Beauty." Herald Citizen[Cookeville] 12 Aug. 1965. Print.

By Charles Denning

Hardscrabble may not sound like the name of a fascinating scenic wonder.

|

Through (sic) ‘hardscrabble’ is not a word in the dictionary (1), anybody in this part of the country probably has a good idea what it means, whether he is able to put it into words or not.

The word has a rural flavor, suggesting rough, stony land, a tough place for a farmer to make a living.

“I first saw the word in print a couple of years ago,” Robert Hawkins said. “I was on a plane trip and picked up a copy of LIFE magazine. Reading an article about Lyndon Johnson and the LBJ Ranch, the country around there was called ‘hardscabble land.’ Out of the gray past, without an orgin (sic) which can be definitely cited, the word had been applied as a name to a spot of geography not far from Cookeville.

Guided by Hawkins, of Algood, a son of William Hawkins, on whose farm in the southeastern corner of Jackson County Hardscrabble is located, we went there. Hawkins’ farm is just off Highway 135 to Gainsboro about 10 miles northwest of Cookeville and near Dotson (sic) Branch church and Cemetery.

Its ruggedness is the first thing you hear about Hardscabble. The approach through the fields in back of Hawkins’ barn, through the woods and winding into the hollows is not taxing. Getting down into the gorge and out again is a matter a bit different.

Second thing you’ll hear about Hardscrabble is the legend of the strange, brutal killing by moonshiners of a crippled boy who had innocently wondered upon their still in search of his mother’s cow.

With us went three boys, Hawkins’ son, John, and Randy Fields, and Mike Mabre, and an assortment of hounds, Plott, and beagle. The day was bright as the face of a new coin, sweet as an oboe tune, somewhat cooler than usual. The late-July sky, blue as October, was streaked sparsely with gauze-like clouds.

Beside blooming tobacco patches and tussling cornfields we passed, over what Hawkins called “stagger road” – the trail once taken by moonshiners coming from Hardscrabble with jugs slung in pokes over their shoulders. We found Hardscrabble a rock-ribbed canyon with the Dotson (sic) Branch falls, a stepped cascade at its head and a peaked, treacrowned (?) rock formation, unofficially (2) called “the pinnacle” near the mouth of the gorge.

Crossing the branch we took a twisting trail once plied on horseback by the late Walter Smith, of Cookeville, a mail carrier, down into the gorge at the foot of the falls. Orville Woolbright, who has a store now in the Dotson (sic) Branch community, once ran a mill on Hardscrabble Falls. Climbing the trail to “the pinnacle,” we crossed under a high, overhanging bluff and there found neatly stacked rocked slabs which has years ago enclosed the first pit of a still. Earlier we has learned that it was not at this still but at one under Pole Bridge Creek falls in a nearby hollow that the crippled boy had been boiled alive.

Up rock shelves we shunted to “the pinnacle,” which rises high and stands like a forecastle of a ship jutting into a swaying canyon. Not a mile from paved roads, the country is wild and lonely. On the wind-swept top we saw cedars dwarfed and maimed by gusts that sweep from the stony canyon. Somewhere a bird cried, “Sharp! Sharp! Sharp” – a judgment which struck through the leafy woods like a hammer on an anvil. But the birds tell nothing, nor the trees, nor the sky. Not even the wind, rushing out of the secret gorges silent as burial crypts, through (sic) it sometimes seems about to, like lips which tremble tensely on the verge of speech.

Under an overhang, we noticed crystallized alum (3) like white crusts and exposed mineral patches yellow as marigolds, rocks scaley with flakes of gray-green lichen.

After Hardscrabble, we trekked to the Pole Bridge Creek, down through a steep woods to the shallow, gravely stream, which we sloushed through to the falls. The cool stream flowed clearly, quietly. Minnow schools scattered shyly here and there in formation. Once a large fish, seen as little more than a shadow, hurried under a submerged rock. And the dogs routed a varmint of some kind, had a few minutes of excitement and ended up with nothing, milling about sheepishly.

Opposite Pole Bridge falls is Dave’s Bluff, named after one Dave Hamilton, reported to have died in a fall from the bluff one night years ago. Unable to reach the bottom of the falls, we learned over and peered into the chasm and the shadow under the overhang. We could spot no trace of the sill where the boy had been murdered. According to legend, pieced together from several sources, the crippled boy was searching the hill and hollows for his mother’s cow, strayed from her pasture. Tracing reports of those who said they had heard the cow’s bell, the boy happened upon the shiners, who apparently feared he would turn them in.

Opinions vary on how long ago the incident happened, from just after the Civil War to around 1900. But those who have had the tale handed down to them repeat it, embellished with horrific details, as if they been eye-witnesses. For a week or two, it is said, the boy was kept tied-up in a barn somewhere in the area of the still. Then the shiners, perhaps in a fit of drunkenness, made up their minds to destroy him. The (sic) built a fire under the mash boiler and, when the water was hot, stuffed the boy inside. In a wretched mania, the boy kicked the lid off. But one of the men replaced the lid, climbed up and sat on it until the spasms inside the boiler finally ceased. The boy’s bones were buried under a rock near the 50-foot, pony-tail falls emptying off the bluff above the still.

One account tells of an old man who, later, collected the bones and kept them about his place in a grass sack. The bones finally were throws back into Pole Bridge Creek, washed over the falls and lost it is said. Those who tell the story state positively that none of the men involved were ever charged with the crime. But there is one ending to the story, maybe invented by an over-zealous moralist, which contends that each of the shiners met retribution, as they died particularly bitter deaths. For instance, as the man who had sat on the lid died, four of five were required to hold him on the bed. “I see the crippled boy!” he screamed pleading, “Don’t let him get me! Don’t let him get me!”

“Hardscrabble,” the word seems to enclose all this in its meaning. And the legend of the crippled boy seems to fit well into the country both harsh and desolate and beautiful.

Notes

1) Though hardscrabble may not have been in the dictionary when this was written, it currently is and means "not having enough of the basic things you need to live" according to the Oxford Learner's Dictionary. URL: https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/us/definition/english/hardscrabble?q=hardscrabble; Accessed: 6/22/21.

2) The name Hardscabble is now officially the name of the pinnacle and the waterfall.

"U.S. Board on Geographic Names" U.S. Board on Geographic Names (BGN). N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Mar. 2014.

3) Old-timers had told me about "alum" under the overhands of bluffs before. They said it was collected and sprinkled on their fields as fertilizer. I saw the crystals when visiting Hardscrabble a few years ago and decided to satisfy my curiosity. I collected a sample and had it run through the XRD device at TTU. It came back as almost entirely gypsum. Here's a photo:

More Hardscrabble photos:

Comments