The Eastern Highland Rim - Part 1 - Geology

- Pennington Formation

- Bangor Limestone

- Hartselle Sandstone

- Monteagle Limestone

- St. Louis Limestone

- Warsaw Limestone

- Fort Payne Limestone

- Chattanooga Shale

- Calcite

- Chert

- Gypsum

- Quartz

- Crinoids

- Brachiopods

- Corals

- Stromatolites

Table of Contents

How it Got Here

Geology

Minerals

Fossils

Regional Geology Presentation (2 hours)

How it Got Here

During the Mississippian period, approximately 380 to 320 million years ago, the Eastern Highland Rim was formed through the deposition of sediments. At that time, a large, shallow sea covered the interior of the United States, providing a habitat for corals and other creatures that primarily created their shells from calcium carbonate. As these organisms died, their remains accumulated on the ocean floor, forming deep layers of limestone that have full of aquatic fossils. In other places, the shells dissolved and deposited as lime mud.As the continents shifted and ocean levels dropped over time, the Cumberland Plateau and the Eastern Highland Rim moved westward and up in elevation. The sediments of the Cumberland Plateau, which largely consist of stream deposits from the former Blue Ridge Mountains, formed a protective layer preventing the complete erosion of the limestones that make up the flank of the plateau.

Geology

Stratigraphic Column - A stratigraphic column shows layers of rock from top to bottom for a given region. The whole of White County (shown below), and much of the Eastern Highland Rim follows the same pattern of rocks layered atop one another much like a stack of pancakes.The rock units that comprise the Cumberland Plateau are shown in warm colors, where the Eastern Highland Rim is shown in cool colors.

The rock units are ideally separated by identification of fossils within each unit. However, in this article I will discuss more broadly the geomorphology of the rocks and the landforms associated with each unit.

In the below geologic map of White County, Tennessee, the stratigraphic column begins with the Pennsylvanian aged Rockcastle Conglomerate and as one loses elevation, one encounters new rocks. Warm colors were used to indicate Pennsylvanian aged rock, which comprises the Cumberland Plateau while cool colors were used to denote primarily Mississippian rocks comprising the Eastern Highland Rim.

Pennington Formation

The Pennington Formation is a heterogeneous sedimentary rock unit consisting of sandstone, limestone, and shale. While these materials can be found across the layer, certain areas tend to have a preference for one type over another. A notable outcrop of the Pennington Formation can be found along Highway 70 between Sparta and Crossville, characterized by several layers of siltstone and limestone. Although the formation is known to produce caves, it is not as abundant as neighboring stratigraphic units. However, it can give rise to unique sinking streams at higher elevations near the Cumberland Plateau.

Bangor Limestone

The Bangor limestone is one of the main cave producing units on the Eastern Highland Rim. Along its upper contact with the Pennington, pits can be found.A special configuration of karst window occurs between the Bangor, Hartselle, and Monteagle units where an upper cave (occurring in the Bangor) has an outflowing stream. The stream travels a short distance and drops off the edge of the Hartselle into the Monteagle. Example of this include Virgin Falls, Sheep Falls, Rainbow Falls, and many more. When this happens underground, it is often associated with especially deep and significant cave systems.

Hartselle Sandstone

Aside from the lenses of sandstone within the Pennington Formation, this is the only sandstone in the regional Mississippian stratigraphy. It's a thin unit, and usually thinly bedded with plenty of crossbeds. I most often think of it as providing a "bench" halfway up to the Cumberland Plateau where one finds flattened areas along the escarpment (like here, and here). It provides a basement unit for Bangor Limestone cave and a ceiling for Monteagle Limestone cave. It's also the stone from which comb graves are hewn.The Hartselle Sandstone / Monteagle Limestone contact is the most prolific cave producing region accounting for approximately 70% of the caves in Tennessee. It tends to produce short caves with jagged limestone that are muddy. These are often miserable caves, but if you can get into them deep enough they can get interesting.

Monteagle Limestone

This rock unit is very soluble. It's easy to identify the contact simply by noting the grey-blue boulders at the surface. This occurs because so much of the rock weathers away that little soil is left behind. These boulder fields are often steep and generally wooded because no one wants to scramble around on steep boulders cutting trees.As a result of this units solubility, it is the most prolific cave producing unit. Tennessee's longest cave, Blue Spring, is formed in this strata. Most of the other long caves in the state are also formed in this rock unit - Cumberland Caverns, Xanadu Cave, Rumbling Falls Cave, Mountain Eye System, Nunley Mountain Cave, Big Bone Cave - to name a few. In other states, the Monteagle goes by Ste. Genevieve and Gasper Limestone. Mammoth Cave, the world's longest cave, found just north of Tennessee, in Kentucky, is formed in the Ste. Genevieve and St. Louis limestone (mentioned below).

The Monteagle doesn't tend to form as many sinkholes as the St. Louis or Warsaw units, but the sinkholes which are in it are spectacularly huge, and often the deepest and largest volumetrically.

St. Louis Limestone

In the regions where the St. Louis limestone is on the surface, one can note that few (surface) streams are present. This results from the combination of being easily soluble, as well as having an layer of chert which forms an aquatard. Streams will flow across the surface of an aquatard, which is situated within the rock unit. So what we tend to see are underground river systems, as opposed to surficial streams.Because rivers are very dynamic systems, it's not uncommon for the systems to change on human time scales. In February of 2014, a sinkhole swallowed part of the National Corvette Museum as a result of a collapse within the St. Louis limestone.

The St. Louis limestone tends to form many sinkholes on the surface. While they are not as large volumetrically or by area as sinkholes in the Monteagle, they are larger in number.

Warsaw Limestone

The St. Louis and Warsaw are similar in appearance, and for their propensity to create sinkholes. To quickly tell them apart, the Warsaw tends to be a sandier limestone than the St. Louis and in places shows evidence of crossbedding.Much like the St. Louis, many wet caves exist within this unit, and as a result this rock unit tends to produce a large number of sinkholes.

One notable sinkhole in the Warsaw limestone happened in 1994, in Cookeville, Tennessee, when a large collapse exposing a previously unknown cave system (Tires-To-Spare Cave - which is a whole other fascinating story).

Fort Payne Limestone

The Fort Payne Limestone is generally encountered as a cliff above a waterfall. The rock tends to be a very cherty limestone that is both mechanically and chemically resistant to weathering. It is a hard rock, but also brittle, sometimes flaking into shards sharp enough to cut.The Fort Payne is associated with waterfalls because it is underlain by the Chattanooga shale, a rock that is much more susceptible to mechanical weathering. Where streams cross the intersection of these two units, there will always be a waterfall. Notable examples of this include Burgess Falls, Cummins Falls, Waterloo Falls, and Window Cliffs Falls.

On the below picture of Burgess Falls, on the left part of the image there is an obvious change in the rocks around the rim of the waterfall. That is the contact between the Fort Payne and Chattanooga shale. Below the shale, but harder to differentiate in the photo, is the Leipers-Catheys formation, an Ordovician unit.

The Fort Payne in places tends to produce quartz geodes, some of which can be quite large! But I won't give away my favorite geode hunting locations to the internet, so good luck finding them!

Chattanooga Shale

This black Devonian aged shale provides hints of the story of the late Devonian mass extinction. The Devonian is when trees showed up, and their spread across land caused massive amounts of nutrients to be washed into the sea. These nutrients were believe to have caused an algal bloom (not unlike what we see today) and that bloom removed oxygen from the water, killing 19% of all families and 50% of all genera. The blackness of the shale results from its deposition in an anoxic environment providing us with the evidence of a causal factor of this extinction.The Chattanooga shale is known to be one of the most radioactive black shales in the United States due to it containing uranium. This unit was explored by the Manhattan Engineer District and later, the Atomic Energy Commission, for suitable fuel for nuclear weapons and energy.

The uranium content of the Chattanooga shale presents potential health problems though to those who live in the area. Uranium's radioactive decay produces radium, which decays into radon. Radon travels through joints and fissures in the bedrock and settles in low lying places (caves and basements) where when inhaled for long periods of time can cause cancer and respiratory illnesses.

Minerals

Calcite

This mineral occurs throughout caves in the region generally in the form of a cave formation, such as a flowstone. Its occurrence is most often the result of precipitates of mineral laden water (think: the ring on your bathtub).

Chert

This mineral is found throughout the Mississippian limestone beds in lenses and amorphous shapes. Sometimes it is a trace fossil, as the worm burrows from the image below from taken in the Root Cellar in Blue Spring Cave. Many well preserved fossils in this strata have been silicified, where the organic carbon is replaced by silica.

Gypsum

Gypsum's occurrence is primarily in remote, dry locations in caves where it produces unusual shapes like flowers. One of the most unusual forms it can be found in is the beard, comprised of millions of loosely fitting interlocked tiny needles. Beards of gypsum are incredibly delicate, and can be seen to move simply by breathing on them.

Quartz

Quartz vugs occur frequently in the Fort Payne formation. Along the flanks of cliffs, these nodules weather out and fall to the ground appearing as brain-shaped rocks. When sufficiently large, these geodes can be broken open to reveal beautiful quartz crystals.

Fossils

Crinoids

Staples of the fossil record in Middle Tennessee, crinoid stalks are easily recognizable as hollow tubular structures between 3/4" and 1/4" thick. Less often preserved are the flower-like heads, or calyx, that are pictured below. Despite looking like a plant, these are actually animals, and are still alive in the oceans today.

Brachiopods

Brachiopods are another common fossil along the Eastern Highland Rim.

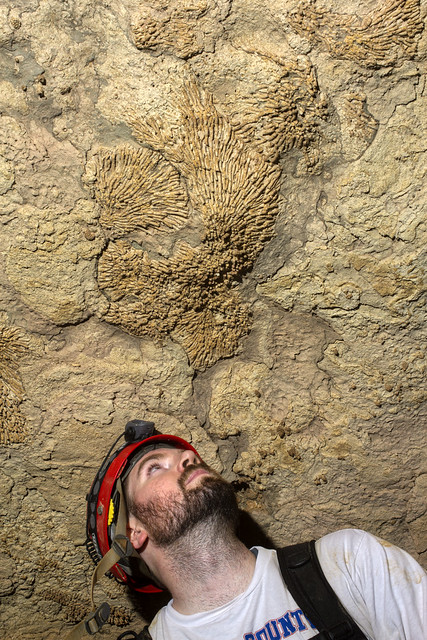

Corals

The Mississippian was a good time to be a coral. I have personally seen dozens of species from across several of the strata on the Eastern Highland Rim. One of the most common, the Rugosa, would form colonies of interlocking hexagonal polyps. When alone, their form looks like a large, slightly curved claw.

Stromatolites

Not exactly a fossil, this trace fossil is the remains of blue-green algae that grew in concentric layers above silt and sediment, creating a algae-sediment-algae sandwich. Stromatolites have largely disappeared from the Earth since many things can eat blue-green algae, but there are still a few places which prevent predation on the colonies.

Comments