Longwave Light on Cave Formations

Last year I purchased a handheld longwave light in the hopes that it would assist in non-destructive mineral identification in caves. The model I purchased was Convoy S2+ Nichia 365nm UV LED 1Mode OP Reflector Flashlight since it ran on 18650 rechargeable batteries and seemed of rugged construction. After having been caving with it for more than a year I've found it to be rugged enough for my typical caving trip, though I generally carry it in a pelican case with my camera. It is lightweight, and doesn't seem to drain the battery quickly, though I use it only for a handful of minutes on any given caving trip.

To no one's surprise calcite is the dominant mineral in the caves of Middle Tennessee that I frequent. Trace impurities within calcite which can color it dramatically in visible light do not significantly change the phosphorescent color spectra. Other minerals present in caves of Middle Tennessee include chert (which does not phosphoress), dolomite (which reflects purple under longwave), and gypsum (which with phosphoress green the same as calcite).

Painted light from my headlamp (white balance adjusted)

Actively painting the formation with the longwave light

Phosphorescence from mineral after turning off longwave light

The top image being what one sees in the "natural" colored light of one's headlamp, or if we were standing outside holding it under sunlight. The following image is where the mineral is being actively excited by the longwave light. The final image is the afterglow (captured small bit by small bit in numerous photos stacked in Photoshop), which is the most diagnostic of the three images in terms of mineral identification. Note the location of red color in natural light is slightly visible in the other images.

Illuminated by an external camera flash

Actively painting vugs with the longwave light

The lack of phosphorescence in this example is what I believe to be so striking.

Painted light from my headlamp (white balance adjusted)

Actively painting the formation with the longwave light

Composite of the previous two photographs

This sequence shows that only a portion of the gypsum is phosphorescent, but I have no explanation why other than perhaps there is a patina on the surrounding gypsum blocking the longwave from exciting the mineral. This would suggest that older formations don't phosphoress where the younger ones do.

The research leaves me with more questions than answers.

To no one's surprise calcite is the dominant mineral in the caves of Middle Tennessee that I frequent. Trace impurities within calcite which can color it dramatically in visible light do not significantly change the phosphorescent color spectra. Other minerals present in caves of Middle Tennessee include chert (which does not phosphoress), dolomite (which reflects purple under longwave), and gypsum (which with phosphoress green the same as calcite).

Example 1: Flowstone in Blowhole Cave

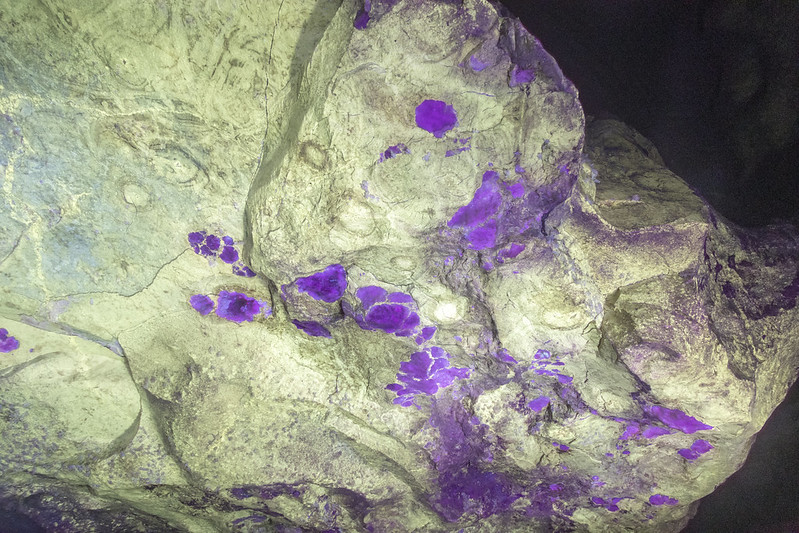

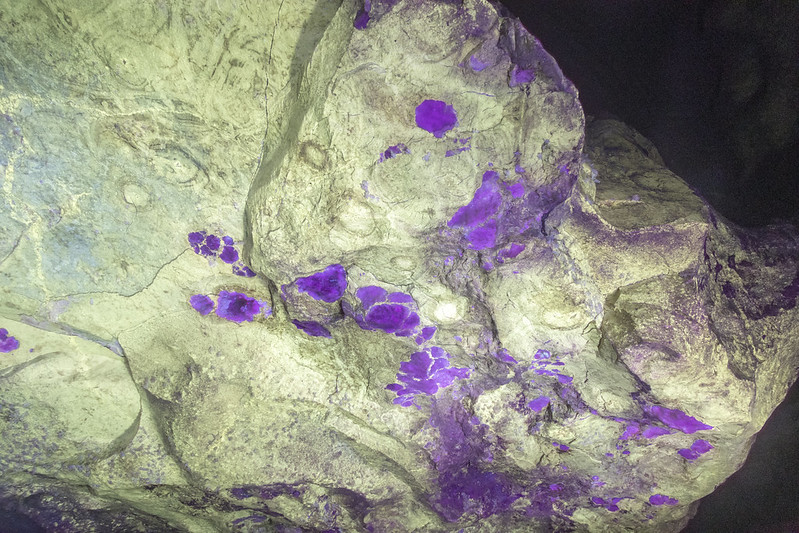

Painted light from my headlamp (white balance adjusted)

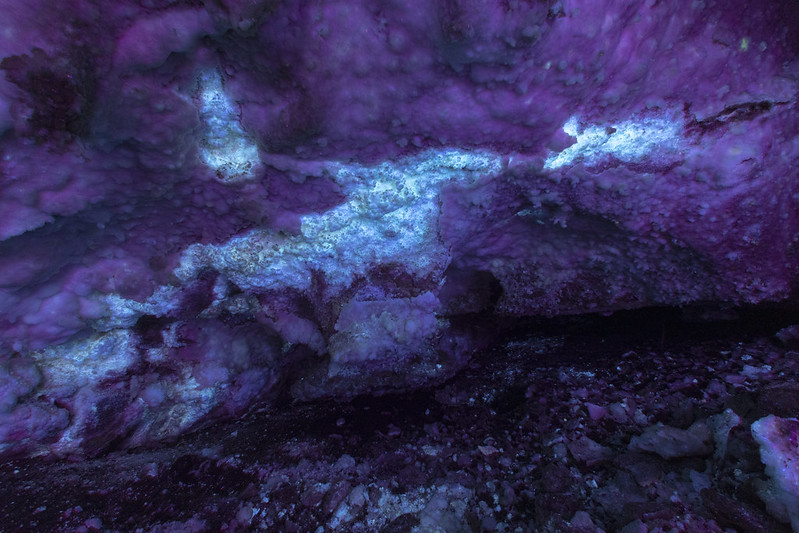

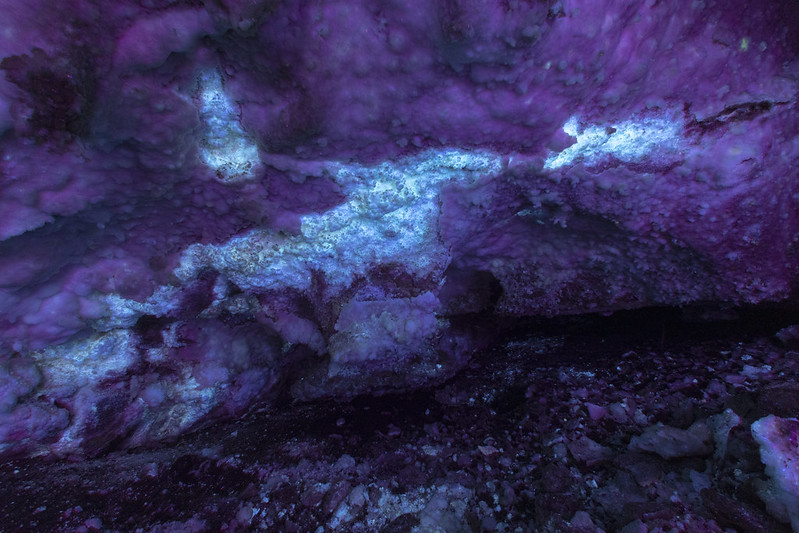

Actively painting the formation with the longwave light

Phosphorescence from mineral after turning off longwave light

The top image being what one sees in the "natural" colored light of one's headlamp, or if we were standing outside holding it under sunlight. The following image is where the mineral is being actively excited by the longwave light. The final image is the afterglow (captured small bit by small bit in numerous photos stacked in Photoshop), which is the most diagnostic of the three images in terms of mineral identification. Note the location of red color in natural light is slightly visible in the other images.

Example 2: Dolomite vugs in the Bangor Limestone in Gourdneck Cave

Illuminated by an external camera flash

Actively painting vugs with the longwave light

The lack of phosphorescence in this example is what I believe to be so striking.

Example 3. Gypsum crust in Cumberland Caverns

Painted light from my headlamp (white balance adjusted)

Actively painting the formation with the longwave light

Composite of the previous two photographs

This sequence shows that only a portion of the gypsum is phosphorescent, but I have no explanation why other than perhaps there is a patina on the surrounding gypsum blocking the longwave from exciting the mineral. This would suggest that older formations don't phosphoress where the younger ones do.

The research leaves me with more questions than answers.

Comments